The metal of the long steel prep table was cold on Stanley’s outstretched hands. He looked down at them and around the galley. The large tins of spices. The gallon cans of beans, boxes of potatoes, giant jugs of olive oil. It was the third day of the quarantine on the USAT Cristobol which still stood in the harbor, but Stanley had no idea that he was in for. He’d boarded the ship just two nights before, followed in all the men just like any other through the maze of piping, bulkheads and narrow staircases. But then in the morning at 0500 he was roused, brought to the galley and told that that he would be in charge of feeding the ship. The mess officer before whose duty this was supposed to have been had disguised himself as a merchant marine and snuck off the ship to call on a young lady in New York City. Lieutenant Huyk looked at Stanley.

“Can you handle this job?” He asked.

Stanley looked again around the galley. He thought of the 1768 men aboard the ship and the fact that he knew little about what he would have to work with and how long he would be responsible for the men.

“Can I have a look around, sir”?

Huyk nodded.

Stanley walked down past the tables to the walk-ins. He opened the door and went inside. From the floor to the ceiling there were hundreds of chickens, packed in like sardines. He looked at the packaging. Southeastern Poultry and Egg Assn. Exp 1/22. On the other side, bacon, eggs, beef wrapped in white paper. And at the far side, produce. More carrots and broccoli than he’d ever seen in his life.

The next room was dry storage. Cans of about anything you could think of. 1200 cans of beans, dehydrated potatoes, 655 cans of peas. 475 pickled beets. Canned salmon, Vienna sausages and Spam.

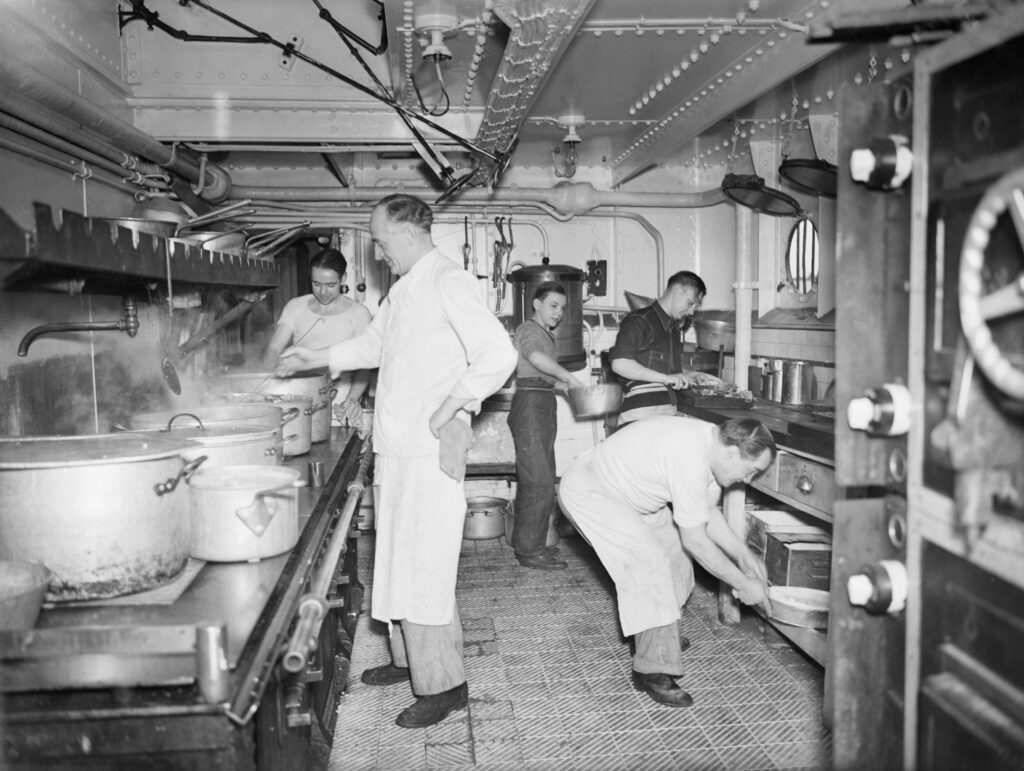

The galley of the Cristobol was extravagant by troopship standards of the time. She was not a quickly assembled Liberty Ship like many of the transports shipping GIs out to the South Pacific or Europe. She was a converted ‘Banana Boat’ requisitioned from the Panama Railroad Co. in 1942. She had 5 decks, a swimming pool, was 495′ 6″ long with a gross tonnage of 10,021 and could steam at 17 knots at full speed.

He went back to galley and the smell and sound of bacon filled air as the 4 cooks had already begun to make the morning’s chow.

“Meet your standards, Sergeant Grimes”? Huyk sarcastically asked.

“Whats for dinner?” Stanley asked, smiling.

“Well, I guess that’s up to you, Mess Sergeant”

And so in his third week in the role of Mess Sergeant for battery D, Stanley took on the role of feeding the Cristobol and all its men on the day before it weighed anchor at Brooklyn Naval Yard. He remembered those days helping out his mom in the kitchen in Kentucky, feeding his family of 12 as a young boy in that small farmhouse. After doing some quick math in his head and looking around the 8 ovens and the time it took to roast a whole chicken, he realized that he’d not likely be spending much time top deck on this voyage. He ordered the cooks set aside 100 chickens and begin roasting them in waves so that they would all be ready by 1800. Stanley’s deployment began in a hot galley on the lower deck of the USAT Cristobal, a ship who he had still never seen given that he had boarded her in the cover of darkness two nights before.

The next morning Stanley awoke to a deep rumble and the bulkheads creaking. The ship was underway. His quarters being on deck one, even if the portholes were not sealed and blacked out he would not have been able to see the outside being below the waterline. As the ship navigated her way out of New York Harbor, he could feel her subtle movement and the sensation made him not sure if he’d be sick. Stanley had never been on anything bigger than a row boat in his entire life, and now here he was crossing the Atlantic with 2000 men … After breakfast had been served and the men back to their quarters, Stanley finally managed to go above deck. He made his way to the bow of the ship. Men everywhere were sitting on deck playing cards, looking out at the sea, excited that they were now underway and speculating where the ship was headed. The sun was well above the horizon by now and the ship moved at a good pace in the calm January seas. He looked around at the horizon. Far ahead there were two Farragut class destroyers which led the convoy. They displaced 1,300 tons each and were armed with five 5″ guns and four 1.1″ anti-anti-aircraft guns. At full speed they could reach nearly 37 knots, twice the speed of the Cristobol . Spread on all sides were 9 other troop transports, each carrying 2-3,000 men. In the center of the group steamed the USS Solomons, a Casablanca class ‘baby flattop’ aircraft carrier whose 16 F4F Wildcats would lift off every morning at sunrise to patrol the horizon for u-boats. The convoy was by no means a large one relative those that landed the troops in the initial waves of Operation Torch just months before, but it was one of the most impressive things Stanley had ever seen. Though he’d seen ships like that in the news or the movies, to see those warships with his own eyes brought a reality to his situation that he had not experienced before.

Stanley caught the rail as the ship jerked suddenly to the right following the lead transport, peeling away from the two destroyers which maintained their straight path. Stanley was confused and watched as the wake of the other ships indicated a sweeping 90 degree right turn. Surely in the broad ocean such a sudden maneuver could not be a good sign. He remembered those stories of u-boat attacks and nervously scanned the sea below.

A merchant marine just down the rail looked over at Stanley and smiled. He could sense Stanley’s apprehension.

“Zig zag maneuver” he said, taking another draw on his cigarette. “No u-boats today.” He offered Stanley a cigarette. “We’ll be doing this all the way over every 8 minutes. About how long it takes one of those bastards to line up and fire.” He gestured to the sea down below. “Hope you didn’t think this trip would be as smooth as the Queen Mary…. If so you may want to ask for your money back”… he joked.

Stanley chuckled and tried to hide his uneasiness even though the man’s humor helped put him at ease.

Convoy UFB-15Z would steam across the Atlantic at 17 knots, or about 20 miles an hour, zig zagging the entire way. The winter seas in the North Atlantic were relatively calm and lent themselves to an expected journey free of ice-bergs that may have broken from the northern seas in the warmer weather. Despite all the protection, it was never far from mind when the men in the galley would lose their footing and sometimes fall into the hull in the early days of the journey as the ship abruptly changed direction that one of those turns may be the ship’s actual evasion of a torpedo. Spending most of his time on deck 1, Stanley figured in the event of an actual u-boat attack, he didn’t have a prayer to make it all the way up and out of the ship alive before the ship foundered.

The men when on deck were required to wear their Mae Wests and every few days were called to all hands drill as if the ship was under attack. The ship did have a cannon fore and aft, but more or less would be a sitting duck under a u-boat attack if not for the escorts. Stanley spent most of those days below deck managing the galley, but when he could went to the fantail to watch the wake of the ship cut its zig zagging path in the sea. Taking in the fresh winter air as the cool grey days passed by, he’d think of Mary Lou, of his family back home. He was concerned that they’d be worried now that they’d not hear from him for weeks.

Late afternoon on the 7th day the men began to hear sounds that they had not heard for several days: the singing of birds. Hundreds of grey brown canaries had perched along the rails of the ship as they approached the islands for which they were named off of the west coast of Morocco. Stanley and some of his buddies whistled back to them and enjoyed a swim in the pool on deck 5 as the sun went down and the voyage entered its last night. That evening if just for a brief time they put out of their mind what was ahead. The idyllic scene couldn’t have been created more perfectly in the movies: the songbirds cheerily whistling as the men splashed in the cool saltwater pool, the sun setting behind them over the glassine Atlantic waters and the two Wildcats lazily buzzing along the horizon almost as if on a sightseeing tour. Their brief moment of illusion was interrupted by the XOs voice over the loudspeaker:

“Attention on deck. Attention on deck. All men topside after sundown are strictly forbidden from usage of cigarettes, cigars or pipe tobacco. Increased risk of enemy activity in the air and sea as the convoy traverses the straights. Landing at Oran, Algeria at 0500, all men should get plenty rest and ready for debarkation at 0800.”

And so Stanley and the men finally knew their destination: Oran, Algeria. Stanley had only heard of it from the article from the Stars and Stripes from just a few weeks earlier reporting on a successful u-boat attack on a British destroyer. Despite officially having been deployed and on the ready for enemy activity outside of New York City, the reality was now setting in that they were entering a war zone. Stanley had read of the vicious fighting across North Africa ever since Operation Torch was unleashed in November last year. The Desert Fox, Rommel, attempting to hold back what was at the time the largest amphibious invasion in world history and the Allies first serious attempt in the West to challenge Hitler’s far flung empire. Intelligence had reported that the landings would not be challenged, but Stanley could not help but picture the clips in the movies reporting the amphibious assaults over the past months in the South Pacific in places like Guadalcanal and Bougainville in which men were unloaded onto remote beaches under a hellfire of machine gun volleys.

That night, despite the orders to get plenty rest, many men went topside to witness an incredible sight coming into view: a mountainous rock jutting from the water to port-side. It glowed in the moonlit night and searchlights cut crisscrossing patterns in the sky from its base, looking for errant night fighters who may be launching their assault from the neutral but Nazi sympathizing fascist Spain. They were passing Gibraltar, the British stronghold at the gateway to the Mediterranean Sea. The water was rough through the straights, making whitecaps on the surface that lit up like tiny flashes all around the convoy, which now steamed at maximum speed and he could see the increased activity of the destroyers, sweeping the surface of the water with searchlights as they arced out ahead of the transports in search of u-boats guarding the straight. A mixture of excitement and nervousness filled the men on the last night before they were to land. What journeys, what dangers lie ahead, none of them really knew. They wondered if they’d ever see home again, and if they did, when that may be. The culmination of all of the past months of training and maneuvers made them feel ready but still unsure of it all. By the time the sun rose, they would be anchored in Africa and going to war.”‘

wonderful red.

One of Erma Bombeck’s quote before her death I remember

“I would have taken the time to listen to my grandfather ramble about his youth.”

You did and it brings us amazing stories from the past

Again, so filled with emotion as I read this. Thank you, Kurt, for paying attention and telling the story.

Thanks for reading! I’ m excited about writing about our expat journey, but the “stanley story” series is my passion project. Here’s the intro to it if you havent seen 🙂

https://vidacolorado.com/introduction/

Waiting on posting the next entry until after i can go to italy and see some of the places he was stationed.