Part VIII – Beneath a Falling Sky

We slept in a large room on straw, men and women. At night we did our business in some buckets, which we sometimes exchanged for pails of water to drink… We ate leftovers from the Americans, which we also collected in buckets.

Antonio Caira, resident of Viticuso, Italy during World War II.

Preface

The story that follows is a blend of fact and fiction. Marco is a composite character who was woven with help from firsthand accounts of Acquafondata in 1944. Sergeant Stanley Grimes, whose smile and voice are etched into my heart, was my grandfather, and he was really there. But in this story, he is an amalgamation of the real man that I knew and the man I imagined on that day. Bringing him back to life in this way has been a joy. His little black dog is real, his job as mess officer and gunner of the .50-caliber machine gun in Battery D of the 67th Coastal Artillery Battalion is real, but the dialogue between him and Marco, and what went through Stanley’s mind as he was firing on the four Bf 109s that winter day in Italy came purely from my imagination. Acquafondata is an actual town that I had the pleasure of visiting in the fall of 2023 with my family, meeting some of its beautiful people and imagining what it would have been like when the 67th CA was stationed there during that harsh winter of ’44. The letters between Stanley and Mary Lou, which became in large part the inspiration for this series of vingnettes about my grandfather’s tour of duty (and where the name “Letters Home” comes from) are all actual excerpts from this very personal correspondence which reveals the budding romance of these newlyweds. In accordance with her wishes, as she told me many times, the letters now lie at the foot of Mary Lou’s casket, so she can be close to them and to Stanley forever. It’s a love story that created my family and one that I am privledeged to be able to glimpse, and share with you, seventy years later.

January 1944. Acquafondata, Italy

“Corri, Marco! Corri!” the old man shouted.

Marco looked at his mother, lying there, eyes open, silent and still. He imagined that her eyes were asking him for something – help, perhaps, or maybe she wanted him to leave. He didn’t know.

“Mamma!” he cried, gripping her in his arms. He clung to her, pressing his face into her chest, hoping his tears might bring her back. Of course, that would not happen. She was warm, but she was gone.

The sharp crack of rifles and the dull thud of pistols silencing the last of the surviors with their wooden butts mixed with the human cries of the villagers. The air burned with the smell of gunpowder and blood.

The old man’s voice called to him again. “Corri, Marco!”

Marco turned and saw a soldier coming toward him. Eyes fixed on Marco, the man held a pistol, cold and sure. The arm lifted, slowly, with the barrel pointed right at him.

Marco shut his eyes.

“No! Per favo—”

He woke up, gasping. He was not in Collegluno, the tiny village up in the hills from Acquafondata, but in the barn. It was still dark, but for thin shafts of light through the door. The old wood weathered through the years letting through the morning light. The air was thick with the earthy smell of animal manure and the dry, bitter scent of burning flour from somewhere far off.

He lay, without moving in the straw, his breath coming back. He didn’t want to wake the other boys. The nightmare faded, but only into another.

The Rossis’ Barn

The cold had settled into the mountains and to keep warm he had to lie with the other children in town who had gathered in the Rossis’ barn. Since the Germans had abandoned Acquafondata a month ago, life had brought a new set of challenges. The soldiers of the French Expeditionary Corps were in many ways no less harsh than the fleeing Wermacht, and to make matters worse, the Germans, grossly undersupplied and preparing for a desperate winter had taken with them all the goods and provisions they could handle. The meager stores of food the villagers had saved that fall had been plundered. The invaders took their blankets, their tools, their medical supplies, and any goats that had not been hidden in the forests. Finally free from the grip of fascist Italy and Germany, they now faced their most desperate trial of the war: surviving the winter of ’44 with barely any of what they needed to live.

At seven, Marco had to find his own way. He was learning to be a man. His parents were gone, killed by the Germans at Collegluno. Other children still had their mothers or fathers that winter, but he had no one. The villagers tried to help – they had all known him, the lively boy everyone liked – but no one had much to give.

He learned how to find food, how to keep from being bullied or taken advantage of by the strange men now in town. He heard that some of the girls had spent nights with them to keep warm. He thanked God he hadn’t needed to, and he kept his distance from them all.

The barn where the eight boys slept smelled of stale hay, goats, and urine from the buckets they used to relieve themselves at night. Some families had hidden in nearby caves when the Germans took the town, but most had returned, seeking refuge together now that the snow had come down hard, sharing their misery somehow made it more bearable. The Germans, afraid of being trapped as the Allies pushed closer, used the worsening winter as cover for their retreat, finally allowing the villagers to return to their homes.

What should have been a peaceful winter scene had turned to chaos. Before the Germans left, they broke down doors, raided pantries, and took what little the villagers had saved for the winter. Marco had watched from the edge of the woods that gray December afternoon, snow falling, as some of the braver – or more foolish – townspeople tried to stop the soldiers.

He had seen Marta the baker wrestle the enemy for a sack of flour. The soldier slapped her hard enough to send her to the ground before he hauled away the last of her supply.

And then they were gone. Marco watched the last truck disappear down the mountain road to the north. He felt an enourmous relief. The oppressors were gone. Finally.

For the first time in weeks, the villagers gathered in the streets to laugh, speak freely, and move without fear. They broke what little bread they had and shared their stories. Old men gathered in the bar, passing around a bottle of grappa one of them had successfully hidden from the Germans. It warmed them as they talked about peace – a fragile thing they barely remembered.

It had been over twenty years since Mussolini came to power. The boys in town had never known peace. The old men could remember it, but barely.

But a new enemy was coming. Even as they drank their grappa, the snow was coating the streets of Acquafondata in a white blanket. The old men sat by the window and watched the snow fall, lit up by the oil lamps in the plaza.

“The Americans are in Venafro,” one said.

“It’s a long way off in this snow.”

“Nonsense. They’ll be here by tomorrow afternoon.”

“And the Germans? They’ll be stuck in Cassino all winter.”

“Cassino, Rome, Milan, what does it matter? The war’s over for them.” The old man stared into his glass. The thought of a world without war warmed him more than the drink.

“Che importa? There’ll be another Mussolini next year. There’s nothing new under the sun.”

They sat in silence, pouring another drink. The barkeep came over, a bottle of Fernet-Branca in hand.“The Germans didn’t take everything,” he said with a grin.

“Why not? While the sky is falling,” one of them said, motioning for the bottle.

Late into the night, the old friends stumbled into the plaza. The only sound was the crunch of their footsteps in the soft snow, and their cursing as it spilled into their loafers as they made their way home in the darkness. The silence, with their occupiers gone, felt strange. That night, against their better judgment, they pretended the peace would last.

February 1944. The American Kitchen

Marco scanned around the barn in the dim morning light. Hunger made him get up. He stumbled over the other boys who lay close together for warmth, and wondered what he would do. He had never known this feeling before. He had grown up simply, but until now he had never feared dying of hunger.

He thought of the soldiers lined up at their mess. The laughter. The smell of coffee and bacon that sometimes drifted up the hill when the wind was right.

He grabbed the two buckets they used for urine and stepped out into the cold. As he dumped them by the roadside, he kept waiting for a soldier to shout at him, or worse.

The snow had piled up against the trees, and the cold made Marco’s teeth ache as he trudged down the windy road. The American detachment had been camped below since last month. Three big guns stood there, their barrels pointed at the sky, and a few men moved about in the gray February morning.

Of the several large green tents, one displayed a large red cross, and another featured a long metal stovepipe curling out white smoke. Marco felt his heart racing out of fear and excitement as he walked down toward the camp.

The eastern sky lit up the hillsides, and the snow sparkled where the light touched. Marco found a stand of trees and waited. Soon the soldiers would head to the kitchen, but after they were gone was when he would make his move.

He crouched there behind a bush, his eyes following every movement. Nervous they might see him and think he was a spy, he steeled himself to go on. But boys had been hanged for less when the Germans were here.

After what seemed like hours, the men began to leave the mess tent until only a few were left there cleaning up, and it seemed to Marco that these few now held his life in their hands. Slowly, carefully, he approached the tent, pails in hand and looking as pitiful as he could – which was no difficult task.

As Marco approached, a man in a cook’s apron came out, holding two bags of trash. The startled soldier yelled “Shit!” and dropped the bags. The boy froze in place.

The man’s expression softened as he noticed that the boy, his breath puffing in the cold air, seemed terrified.

“You really gave me a start, kid!” he said. “Sarge,” he called inside the tent, “better come have a look at this!”

A young man in his twenties stepped out, dark hair slicked back, a pencil mustache above his lip. His boots were laced high, trousers tucked inside to keep the snow out. He had a gentle look in his tired eyes and a warm smile that put Marco at ease.

They stared at each other for a brief moment. The sergeant was curious, and Marco was screwing up his courage. Finally, Marco blurted out what he had prepared to say:

“Famelico. Per favore, signore. Cibo.” He glanced down at the pails, still reeking of urine.

The cook looked at Marco thoughtfully. “If we start this now, they’ll come back every day, Sarge. You know they will,” he said in a hushed voice, as if the boy could even understand if he had heard.

“Jesus, Hilbert. Look at the kid. He’s just skin and bones,” said the sergeant. Turning to the boy, he said, “Mi chiamo Stanley” he said. He was glad for a chance to use the few Italian words he had picked up. “Come ti chiami?”

“Marco.”

“Aspetta.” Stanley took the boy’s pails and went back into the tent. After a few minutes, he emerged with the buckets cleaned out and filled with loaves of half-eaten bread, opened K-rations, and a large link of cured sausage.

Marco’s eyes lit up as he excitedly grabbed the food. “Molte grazie!” he managed to say as he ran off before the soldiers could change their minds.

“I’m telling you, Sarge, he’ll be back. Tomorrow. The next day…” the cook said.

“Well then, I guess we’ll keep filling those pails, won’t we?” Stanley replied, looking at the cook with an attitude that suggested it was an order.

“Yes, sir.” the cook said, wiping his hands on his apron as he went back inside the tent.

Stanley watched the boy disappear down the road. Marco’s little legs struggled as he went up the winding path, nearly dropping the full buckets more than once. He thought of Junior, his youngest brother, who must have been about the boy’s age, safe in Kentucky, thousands of miles away. He wondered if the winter was as harsh there and if Junior was hungry, too, what with all the rationing. Surely not, he thought. But the thought made him miss home.

He looked up at the sky, gray and drab, little flakes of snow blowing in from the treetops. This was a good day, he thought. Overcast skies meant no planes.

A little black dog wandered over, mangy and dirty, looking up at him with hopeful eyes, tail wagging so hard that it wagged her body too. He bent down to rub her head and feed her a small piece of bread. Hilbert would rather see you through this winter than that damned poor kid, he thought, glancing up the road where Marco had vanished around the bend. The boy’s clumsy footfalls left a trail in the new snow.

“We’ll get through this winter yet,” he said to the dog, and took one last look at the sky before stepping into the tent.

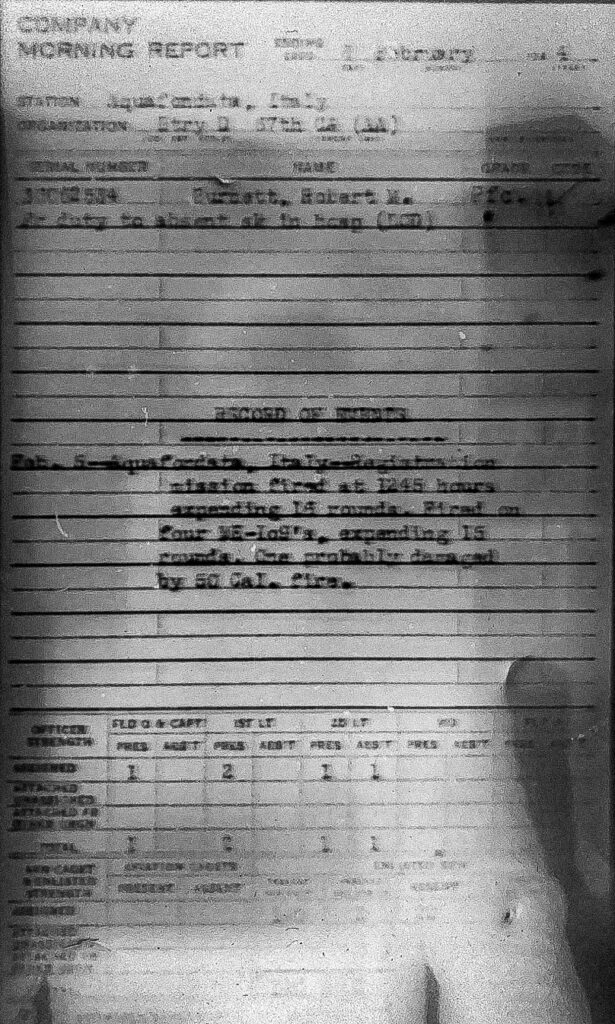

Registration Fire – February 1944

The morning of February 6th began like any other for the 67th. The harsh winter of ’44 showed no signs of letting up. The road out of town to the west was socked in with snow, completely impassable, while the road to the south was well-trodden as resupply trucks of men and materiel, French and American, made their way up the mountain every few days.

It was now half past noon, and after that first encounter nearly a month ago, the local village boys had begun to come regularly with their pails to the American kitchen, begging for the leftovers that the other soldiers refused them, per official Army policy. Often there was little to spare, but Stanley couldn’t bear to leave them with nothing, especially as he could tell from the bitter and dry odor in the air of burning flour, that the French kitchen was incinerating all of their own: he was likely their only lifeline.

The Reconaissance Boys

In the forest west of Acquafondata, a tall, wiry boy in his early teens walked with Marco along the ridge. Lucas, too, had lost his mother in Collegluno and felt eager to prove his worth to the Americans – or maybe it was to avenge that night. He didn’t know which. A mix of excitement and nervousness filled him as the German position came into view through the trees. He glanced at his well-worn wristwatch. 12:30. In just fifteen minutes, it would begin.

He explained again to Marco what the tall man in the American camp had said that morning before they set off: “Five. Five. Five.” He repeated it. Five bangs from behind. Count. Five from ahead. Stop. Then another five. Then another. The man just wanted the boys to remember those numbers and for Lucas to mark on the little paper map where the shells had landed each time.

They watched as men in drab gray uniforms moved about their camp methodically, looking miserable as they trudged through the snow in the clear blue afternoon. 12:41. Lucas could hear German voices drifting faintly up the hillside. 12:44.

“Get ready!” he said to Marco. “Don’t forget the numbers!”

He heard muffled booms far behind them. Thud. Thud. Thud. Thud. Thud.

Almost immediately, a yell came from the camp.

“Artillerie!” The gray men scrambled like frightened ants, disappearing into tiny holes or beneath trucks.

Marco counted.

“Uno… due… tre…” The shells passed overhead in a faint, high-pitched whir. “… quattro… cinque… sei…”

Five booms came down well beyond the camp, leaving puffs of black smoke and dirt in the air.

Sei he said to himself.

The second round fell closer to the camp, and the third fell too short.

They saw the German soldiers still frantically scrambling to find cover, yelling and pointing up the hillside as if at them. The older boy, panicked, yelled, “Andiamo!”

They took off quickly, retracing their path through the snow, grasping at branches and trying to be as quiet as possible as they climbed the steep, rocky hill back to the ridge. Under the drooping branches lay a smooth sheet of untouched snow, marred only by their footprints from an hour ago and the almost-buried tracks of deer and jackals from the night before. The boys knew that if the Germans came in pursuit, they would be easy to track. So they ran all the way home.

The registration fire that morning was routine for the 67th – a way to keep the Germans on their toes, test-firing their weapons, and homing in on enemy positions, dug so deep into the snow that moving even a few hundred feet would be difficult once they were known to the Americans. Although somewhat unconventional, the captain had authorized civilian help in scouting the registration fire. The boys were eager to earn the kindness of the American kitchen, and the Americans were glad not to have to spare soldiers for hiking trips into the unknown Italian wilderness.

The Letter Home

After lunch, Stanley scribbled a note to Mary Lou.

Hello Honey,

How are you? I received your letter today and was sure glad to hear from you. That was bad about Everett. I just got a letter from him a few days ago. Did Mary Kay ever go and see him? Is baby coming along by now? I would sure like to see him. Well honey some day we will have us one. Or two of three maybe. And maybe four of five. Haha… I’ll tell you another thing I want is a little boy. Do you think we can get one? They say they don’t cost much. Haha. You should see my little black dog. I’ve had her for about three months. She’s just about the size of a big rat. I’m going to bring her back to the states with me if I can. If she’s not too old. Haha.

Too bad I am not coming home. Well any way I don’t think this will last over ten more years, do you? What’s ten years to me? I could stand on my head and do that. No sugar, some day I’ll get out of this army and we’ll make up for lost time. And I don’t think that day is too long off. I don’t know how the news is over there. But everything is coming along just fine over here. So it couldn’t last much longer.

Well darling I guess I better close for this time.. So be good honey. And answer soon and write me a big long letter.

Lots and lots of love,

Your husband Stanley

He stared at his bunk, thinking about the house that existed only in thier dreams, and the children they didn’t have. He imagined the day he’d be back in Kentucky in Mary Lou’s arms. She’d be in a white apron, scooping ice cream in that little shop in Crittenden. He’d walk through the door, sharp in his dress uniform, dark olive drab wool jacket, high-waisted trousers pressed straight, and sweep her off her feet to the cheers of the customers.

But then he was pulled from his daydream.

“Condition Red! Condition Red!” a voice from outside shouted.

He grabbed the carbine beside his bed and ran out. The daylight was blinding. Men were running around in a sudden but organized panic. Four men were already at the 90mm Bofors, cranking at the weapon as its barrel angled upward toward the sky.

He ran to the .50-cal and found his crew of three men already at the gun.

“What’s going on?” he called out over the commotion.

“Sarge, acoustics have a group of Messers coming in at 020. Two miles and closing at 5,000. Four, maybe five of ’em”

“Stations, men! Stations!” the captain yelled, hurrying past the emplacement.

Stanley jumped into the seat on the gun. His training flooded his mind as the adrenaline pulsed through his veins.

“Examining gun!” he yelled.

“Bore in order!” a second man shouted.

“Ammo in order!”

“Water in order!”

High in the sky, four aircraft appeared. From this distance, they seemed slow, almost peaceful. They were coming from the northeast, an unusual approach for the enemy. Could they be friendlies that hadn’t reported their positions?

“Damn those idiots,” he heard himself mutter.

But then they dove.

The drone of the engines pierced the cold winter air. Unintelligible shouts and commands erupted from the men around the battery.

A siren sounded. A calm but forceful voice rang out from a speaker somewhere.

“Red alert! Red alert! Red alert! Stations! Stations! Stations!”

Stanley swung the barrel of the .50-cal toward the sky, lining up the crosshairs with the incoming planes. He focused on aligning the correct concentric circle with the aircraft’s angle of approach and speed. It was a quick process he had drilled on hundreds of times, but with real planes in the air, he was terrified he’d forget something or get it wrong. He expected to be obliterated by a bomb at any second.

Nearby, the giant Bofors roared, issuing their deafening explosions in big black puffs that seemed to burst just above his head as the planes, now recognizable as Bf 109s, dove in. Everything was happening so quickly. Unable to accurately target the incoming planes at such close range, the four Bofors between them fired fifteen shots, none finding their mark before falling silent.

Just a few hundred feet above, the 109s erupted with cannon fire, and the .50s around the camp answered back, creating a chaotic and lethal exchange of steel that made Stanley think the world was coming to an end.

He pulled back on the cold steel trigger handle and the gun roared to life, throwing its 2.3-inch bullets at 3,000 feet per second and 600 rounds per minute. Just a few would need to connect in the right spot to take a 109s from the sky.

In a sudden burst, one of the enemy planes erupted in black smoke, pulling up out of its dive. Shouts of triumph rose among the men as they watched, expecting to see it lose control and crash to the ground. The disappointment was a bitter pill to swallow when the plane swerved upward and disappeared behind a mountain in the direction of Monte Pagano.

In thirty seconds, it was all over. Panting, Stanley looked around to see if any men had been hit by the cannon fire. The spent shells around him steamed and hissed in the snow, while men ran about like frightened children. What the hell had he signed himself up for?

Catching his breath, he reached into a jacket pocket for a Lucky Strike. With shaking hands, he lit the cigarette and took a drag, dropping his head into his hands and thanking God that this was not the day.

Sources:

- Le interviste son state realizzate da Eustachio Gino Mancone – c. 2000. Luigi Manfellotto

- Interview with Agostino Mancone and Eugenio Verrecchia. 2023.

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. “US Army Morning Reports. 67th CA. 1943.”

- Excerpt from Stanley Grimes’ Letter to Mary Lou. 1944

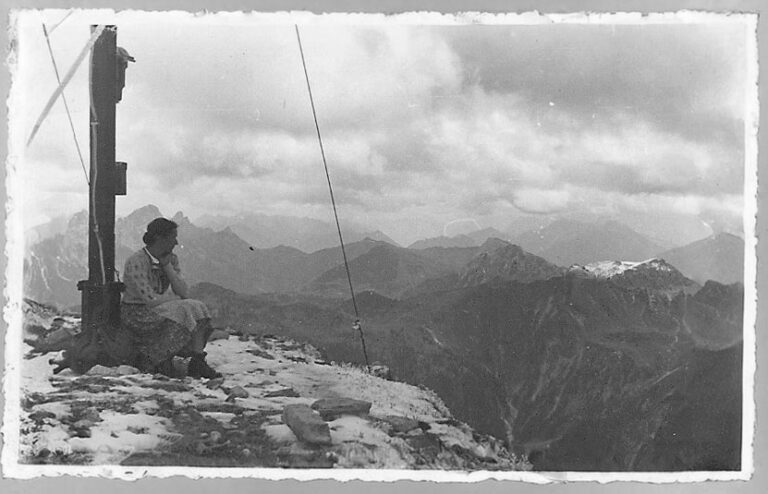

- Photo From Stanley Grimes’ collection. Date and location unknown