Letters Home - Part III - Going to War

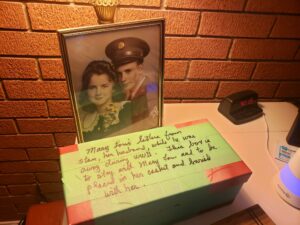

As we stood over Granny’s bed in the hospice room we knew she didn’t have much time. Her body was frail, she had not been eating or drinking for days. The Lord was calling her home. Next to her bed, a shoebox and a second small rectangular brown box. In the shoebox: love letters. Dozens and dozens of them. From her girlhood boyfriend and soon to be husband: Staff Sergeant Stanley Grimes. And in the small box a corsage. The same flowers she wore on her wedding dress for photos in 1942. These things she had kept by her bed for seventy years. They were something she always said gave her peace. That she wanted in her casket. They reminded her of her lifelong romance and that boy that she fell in love with in Kentucky who came back home from Arizona a man in 1939 and told her he would never leave her side.

The shoebox brought the hospice nurse to tears, she said. She was no stranger to death, but she’d never seen something that moved her as much as that shoebox of love letters that Granny had kept all those years. She said it reminded her of The Notebook. I haven’t seen that one so I can’t vouch for that claim, but yes, the bond of Mary Lou and Stanley was special and that shoebox showed me why.

As I stood there by Granny and looked at the box, the wedding portrait of the young couple with Mary Lou not yet even in her twenties, I held back tears in my best attempt to not turn into a blubbering mess in front of the tough-as-nails Uncle Paul, my mom, and Aunt Meg, Mary Lou and Stanley’s first child.

I thought for a moment of reading her one of those letters just to know that some of the last words she would have heard would have been the words of her beloved Stanley… but I decided against it, partly because I am sure I could not have gotten through one, but mostly because I realized that this recital would have been more for me than her: those letters were written on her heart. She didn’t need anyone to remind her of Stanley’s love.

I left the room knowing that this would probably be the last time I saw Granny, and sure enough it was. I flew back to Denver the next day and learned she had passed in the morning. The teenage love story that burned for 70 years between Stanley and Mary Lou had finally come to an end.

10 November, 1942. Eastern Maryland. 2042 Hours

The convoy rumbled down State Route 301 and Stanley could see the lights of Washington, D.C. glowing in the distance off to the West. He and the unit were on their way south from Ft. Hancock, New Jersey where they had drilled on setting up beach fortifications and monitored the night sky over the Atlantic as DC-3’s buzzed around New York City coming in to land at LaGuardia Field.

He and the boys would track them with the sights of the Bofors 75mm machine gun as if they needed to lay down a base of flack to stall their approach. Niether Stanley nor his commanders knew where the 67th CA would deploy, but the message being sent seemed to be that wherever it would be, there would be a lot of sand and coastline. Not a day went by that he and the boys did not have to pour sand from their boots and dungarees… they lived in it, drilled in it, and when time allowed, played in it.

Stanley focused his flashlight on the small parchment in front of him on his lap and wrote to Mary Lou:

My dearest wife…. Just a few lines as I am thinking of you… Honey I had a dream about you last night. I didn’t work this morning and when one of the other cooks got up this morning at 4 o’clock I was talking about you in my sleep. Darling I do love you alot, I love you more every day sweetheart. Honey I sure will be glad when this war is over and we can be together all the time, I don’t think it will last much longer. Honey I would like to write more but I can’t think of anything to say so I’ll close and write next time. Bye sweetheart. Your Husband, Stanley.

Excerpt from Stanley Grimes’ Letter to Mary Lou. Nov 10, 1942

The night air was cold but Stanley and the other men stayed warm in the back of the CCKW 6X6 ‘deuce and a half.’ Stanley’s buddies grinned at him as he carefully folded up the paper and put it in his jacket pocket.

“You’re ate up Grimes… and she ain’t gonna be waiting for you after this is over if she’s half as pretty as she looks in those pictures” one of them said.

“We got married last month,” Stanley said with a big grin, “…she’ll stick around.”

The other boys teased him and playfully shoved at his head and shoulders but Stanley was proud and knew they were all just jealous. He was one of the only boys not out running around for young ladies on the weekends, earning him a reputation of maturity which couldn’t be said for many of the boys in the outfit who were a long way from home and eager to spread their wings when given the chance.

Men of the 67th

There was Thomas Carosella Jr, from East Brooklyn who’d grown up in a little apartment above the pizza shop on the 9000 block of Avenue L. His heavy New York accent always sounding funny to Stanley and who always seemed to have a story from home growing up that entertained the farm boys who normally only heard about such things from the pages of Hardy Boys.

And Pvt Ralph Hunter from Metamora, Indiana, whom Stanley met in the CCCs and was drafted that past spring. He was in a different unit but had become Stanley’s best friend in those years away from home. Ralph had an older brother Raymond who was also enlisted and had been deployed to England just a few months ago (although he and Stanley did not know where).

He came from a military family: his father having served in WWI, fighting in the battle of Ypres and receiving a purple heart from Woodrow Wilson. It was good to have a friend like Ralph. He and Stanley would talk about the ice cream shop on Main Street in Brookville or the girls they’d talked to at the films when they got back to town and walked around looking dapper in their dress uniforms, the time that they mailed a lizard back home from the camp in Arizona and the scream Ralph’s sister must have let out when she opened the package. They’d read the letters from Ray and wonder what it was like to have sailed across the ocean and would take bets on how many Krauts he’d already killed.

And then there was Lieutenant Charles Huyck, from Great Neck, Long Island who’d gone to Penn State University and was a member of Sigma Nu fraternity. He got married last June to Miss Jane Witman and was one of the most educated and smart men Stanley had ever met. He was comforted that if he were going to war he’d be following in sharp guys like Lieutenant Huyck.

By 11 PM it had begun to rain and the convoy turned off the road and the driver of the lead truck showed papers to a man in the gatehouse. Fort AP Hill the sign read. United States Army.

The 67th Coastal Artillery Division was formed in July 1940 at Fort Bragg where the boys learned how to be artillery men. How to dig into a position and defend an area from enemy air attacks. They’d already deployed to Paterson, NJ after basic training, defending the New York City area from possible (although unlikely) attacks from enemy aircraft or even the V-1 rockets that had been plaguing the United Kingdom for months.

In hindsight we now know the unlikelihood of any of this coming to be in mainland USA, but in 1940 the 67th CA was prepared for the possibility. At Fort AP Hill the unit began to train for a new mission: not just a fortified position, but field maneuvers and navigation in poor conditions with all of their heavy weapons and ordinance in tow. Stanley and the men knew they’d soon “go over” but did not know when or where… the training they were to take now he could not help but realize was likely the final step before they went. One last skill that would be useful before setting up on a beach in France, a cliffside in England, a farm in Poland or a hill in Africa.

And so the men settled into AP Hill. Stanley got to know the men of Battery D as he never had before. For weeks on end they would disappear into the forest, hauling behind them on horseback four 75 mm AAA guns and six 50 caliber machine guns. The engineers erected makeshift bridges to haul the big guns over the muddy Virginia creeks.

They would be roused from their sleep after midnight and timed on how long it took the whole unit to become combat ready. They learned to navigate by the stars and when none were visible by using crude maps with landmarks on them, made to simulate what it may be like to be in a foreign land with limited information. AP Hill turned out to be a tough place for Stanley to write home given the constant activity.

Well darling, I thought I was never going to get the chance to [write]. We’re on maneuvers now and we don’t have time [because] we’re always in the woods and moving. I think we will be out here for almost three weeks . I don’t mind this so bad… Honey how is your cold? I hope you are over it… tell your mother and all of them hello… I think I’ll be working xmas and we going to have a big dinner. You can guess about a time I’ll have cooking for 200 men and they eat like pigs, all of them. But me. Ha Ha!

Sweetheart if you don’t hear from me for a long time you will know I’m gone over seas. I think we going but I don’t know when. But don’t worry darling, I may not even go at all. Well sweetheart, I can’t think of much to say so I’ll close.

Your husband, Stanley.

Excerpt from Stanley Grimes; letters to Mary Lou. 11/25 – 12/19/1942

The men of Battery D that year enjoyed a grand Christmas dinner together with Stanley behind the chow-line. He served up spaghetti, bread rolls, Weenie Royale (a casserole of chopped onions, soy sauce, eggs rice and weenies) and Spam sushi. Ever since his days in Ft. Bragg, Stanley had taken to the kitchen, first against his will, pulling many days of ‘KP’, or kitchen patrol, in which he’d spend weekends peeling carrots or potatoes while his buddies went into town. He never revealed just what landed him in KP, but I am sure they made for some good stories.

But eventually Stanley not only proved himself adept with a knife and behind a stove, but he also turned out to have a knack for logistics, food costs and the basic nutritional knowledge to keep a large group of young men happy and healthy. In December of that year he’d been promoted the Battery D Mess Sergeant. According to the company organizational handbook:

The Mess Sergeant is a ‘key’ man in any organization and must be selected with great care. He should be above average in conscientious attention to duty and loyalty to his company… because his responsibilities and duties are such that neglect, or even carelessness… will be reflected in a short time in lowering morale of the unit… and may result in considerable financial loss to the company fund. He must be thoroughly honest in order that there may not be any improper handling of rations… and have and imagination in order to plan his meals with variety and taste…

Company Administration and Personel Records. C.M. Virtue. 1942

That Christmas, the men enjoyed a feast. They laughed together, talked about girls, their wives, their brothers. They talked about the latest news of the war. They had read in the headlines a massive encirclement of an entire German army group in a place called Stalingrad. How the Red Army ferociously held them there despite multiple attempts to break free.

While the main source of information being The Stars and Stripes did intend to paint a positive picture of the war effort, it also shared the sinister side: an issue a few weeks before had reported that the USA had suffered 142,872 casualties since the war’s start in December, 1941. He’d read of German U-boat activity: The British destroyer Partridge which had been sunk last Saturday off the the coast of a place called Oran in Africa.

After maneuvering practice, the massive Operation Torch underway in North Africa, and many of the boys reporting that their brothers, friends or cousins had already shipped out… the men of the 67th had a sense that their time was near. That snowy Christmas night in Virginia, miles from home and not a carefully hung stocking to be seen, for some of the men would be their last.

As the evening grew on and the boys finished their meals, the Captain surprised them that they’d show The Shop Around the Corner, a Christmas movie starring Jimmie Stewart that had come out a few years back that all of them had grown to love… If for an hour or two them boys felt like home. With their mothers, their wives, their girlfriends, those they wouldn’t see for years.

]The next day Stanley awoke to sounds of trucks pulling into the front of the barracks and could smell the diesel of their engines grinding to a halt on that cold December morning. He and the men were given a half hour to pack up their limited possessions and report to the ‘deuces’ by 0630 for departure. They left AP as unceremoniously as they had arrived and headed north to where, they did not know.

The boys took bets on where they were going: maybe to a train station in Philadelphia that would take them all the way west to San Francisco for departure to a remote Pacific island. Maybe they’d be loading onto a boat and be a part of the long awaited land invasion of Europe? Maybe joining forces with General Montgomery’s 8th Army in Africa in an attempt to finally put to rest Rommel’s Africa Korps foothold in the continent.

The convoy rolled through Virginia, Maryland and New Jersey, and after a brief stay in a staging area at Ft. Dix, was on the road again. It was New Years Day, 1943 and by nightfall the men knew their destination: the skyline of New York City appeared in the distance. But in an eerie twist, all the towers rose from the streets in total darkness as if ghosts. The whole city was under blackout orders so that the shipping coming out into the harbor could not be silhouetted against the lights and made easy targets for U-boat attacks.

The once vibrant heart of the roaring twenties, the largest city in the world, now sat in the harbor like a sleeping giant. Some of the men, like Pvt Casorella felt a little bit of comfort in that it was in a way a homecoming.

“Wars over boys!” He said. “They’re sending us all home!”

The boys laughed and looked at the skyline of the city getting closer. They were excited. They were nervous. They all knew that the port of New York was where almost all the boys going to the European theater had shipped out from. It was now their turn.

By 2200 the convoy pulled into a huge camp with commotion everywhere in sight. Barracks were still being erected even at night, logistics officers yelled at lost truck drivers in the mass of bodies and vehicles, orders were being yelled at wide eyed recruits jumping from the back of trucks. Camp Shanks, the sign read.

“I heard of this place….” said Ralph Hunter nudging Stanley’s shoulder, “They call it ‘Last Stop, USA…’ My brother shipped out from here a couple weeks ago. Damn…. Just missed him.”

Over 1.4 million GIs were processed through Camp Shanks throughout the course of the war. It had been erected in a short period of time as a holding area for troops on the way to the Port of Embarkation in New York City. Men stayed usually for about of the week before heading to the rail depot and down to the city’s ports. For Stanley and many of the men, it was the last American soil they would see for years, and for some of them, ever. Before going to sleep he scribbled out a letter to Mary Lou:

I’m not at AP Hill anymore and I can’t tell you where I am. I like it here fine [but] our mail is censored what I write to you…sweetheart I’ll be glad when this is over. I [don’t] think it will last so much longer…

Excerpt from Stanley Grimes’ letter to Mary Lou. 1/1943

That night, the men settled in uneasily. But even knowing the casualties, the U-boat attacks, even the letters from home about loved ones lost, the boys were more than anything eagerly anticipating the next stage of their journey.

As Ernest Hemingway would say after returning from WWI after being wounded: “When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you. Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and know it can happen to you.” The uncertainty of what was coming was thrilling. That ship moored in Brooklyn Navy Yard whose destination was still a secret. But the boys were ready to get on with it now that they realized they were being staged and the overseas journey was coming.

Stanley laid in his bunk that night and remembered that drizzly day in Kentucky almost two years ago when he had strolled into an Army recruiting office in Ft Thomas, Kentucky to enlist. His buddy that went with him got cold feet but he did anyway. That picture of Uncle Sam pointing at him saying “I Want You!” He remembered that spring day in Shelbyville, Indiana when he’d enrolled in the CCCs... his mother’s outstretched hand that he didn’t take.

He knew his journey was just beginning, but he already longed for the day when he’d get off a ship after the war and sweep his young bride off her feet so that they could get started on that little home in Kentucky. He closed his eyes. Even at that late hour there was still a mass of activity at Camp Shanks. Men were mustering outside of their barracks and getting in trucks to head to the docks. There was shouting, car horns, the crackle of the kerosine stove in the middle of the bunkhouse that kept the men warm on that cold January night. Stanley was sung to sleep by the sound of America going to war.

Tell me not, Sweet, I am unkind,

That from the nunnery

Of thy chaste breast and quiet mind

To war and arms I fly.

True, a new mistress now I chase,

The first foe in the field;

And with a stronger faith embrace

A sword, a horse, a shield.

Yet this inconstancy is such

As thou too shalt adore;

I could not love thee,

Dear, so much, Loved I not Honour more.

To Lucasta. Going to the Wars. Richard Lovelace. 1649.