Part VII – A Mission in the Mountains

Here it is the same everyday, up at 400 hours, at readiness all day, bombs, air combat, heat flies and to bed at 10.00 in the evening. It it tremendously wearing and one can’t get used to it. I don’t enjoy the southern theater anymore- Carl Pashas 5/jg53

Preface

Before I wrote this post, I knew little more about the German Luftwaffe than what I’d seen in movies or as a side note in stories about the American experience in WWII: villains in their drab charcoal planes, sweeping in for the kill on the hero of the show, or raining terror down on Allied cities. They occupied, in my mind, what could be described as a typical American-centric retelling of the war: inferior, malevolent, destined for defeat due to inadequacies in men, machinery, and strategy.

Not all of this is untrue, but the more I learned about the Luftwaffe, the more I realized what a marvel of a modern military machine it was in its time — one that transformed from a hyper-organized but secretive force in the early 1930s into a battle-tested behemoth of 1.7 million men by 1941. Its pilots, honed not over mere months but years of relentless combat, aviation, and mechanical training, epitomized excellence in their craft. This was a force to be reckoned with — one which many in Europe and Africa would come to fear.

Its leader, the haughty ex-fighter pilot of WWI, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, stands as a stark symbol of both the Luftwaffe’s glory and downfall. Infected by an insatiable desire to impress Hitler and a yes-man to his core, Göring epitomized the sycophantic tendencies pervasive in the Führer’s inner circle that eventually brought a once-formidable force to ruin.

All this being said, the Luftwaffe was, in many ways, doomed to failure given the reckless ambitions of its leaders. By early 1944, it was operating with around 270 aircraft compared to the Allies’ 2,600. Nothing could be done in the face of such vast superiority except a quickly won war on all fronts. But in 1940, this still seemed within Germany’s grasp.

Yes, this air force served a purpose that poisoned the earth in ways humanity had never seen. But the story of the men who piloted these planes — men who in later years fought such an uneven battle so courageously — is one worth remembering. This is not a tribute to their cause but to the men themselves: men with photographs of loved ones adorning their steel cockpit panels, soaring into the heavens with a fervent passion for flight, becoming pioneers in the sky in a world that had never known such a thing.

They were the men my grandfather spent the better part of his early life studying, with the goal of picking them out of the sky. Yet, in his pursuit, he glimpsed their shared humanity. They were men with mothers who cared about them. He would tell me how he took no pleasure in pulling a trigger that hurled giant .50 caliber bullets their way. Such was the reality of the conflict, where compassion wrestled with duty in the crucible of battle.

Stepping Back in Time

In the fall of 2023, I visited the picturesque Italian mountain village of Acquafondata — the target of Kurt Müller’s group of four Bf 109 fighters on the morning of February 5, 1944. The village and its people came alive to me in ways I hadn’t expected. I walked down a small grassy country road where a guide from the Combat Road History Museum held up a laptop and, as we squinted in the sun, showed photos of the exact Allied positions in 1944 against the backdrop of how they look today.

It was fascinating. Just off the side of that road, I could see my grandfather in the mess tent. I could smell bacon, eggs, and coffee in the air, feel the chill that settled into the mountains during that punishing winter of 1943–1944.

It was with this fascination that my retelling of this part of his story transformed. Originally, I thought it would be one post, simply retelling what his time in Italy was like. But this town inspired me to tell it better — or at least more completely.

A few months ago, I attempted to tell the story of its people: the struggles they endured in the winter my grandfather was there, the terrors they suffered, the massacre at Collelungo, in which 42 Italian civilians were murdered in cold blood on a mountainside that fall at the hands of German soldiers (you can see their names here, in this no-nonsense recollection that has evaded most history books). After writing this, the son of one of the only survivors reached out to me — shocked, no doubt, to find some recollection of this 80 years later on a random history blog. Having touched one soul from this time reminded me why this journey was so important: to not forget those who suffered through no fault of their own.

Of course, I also wanted to recreate my grandfather’s experience as I had originally imagined — one shaped by his own retelling and the people and places I encountered. But that left a missing piece: the enemy.

I found the story of why this obscure place became such a focus for both the Germans and the Allies during the war to be deeply intriguing, and looking from only one side seemed incomplete. What follows became part II of a three-part series bringing this section of Letters Home to life — told this time from the cockpit of a Bf 109, the war machine that so menaced the Allies throughout the war.

The Sortie

Setting the Stage: JG 77’s Struggle

Jagdgeschwader 77 (JG 77) was fighting a losing battle — and they knew it. Their confidence in their commander, “Smilin’” Albert Kesselring, known for optimism and composure in the face of overwhelmingly unfavorable odds, had not waned through the winter of 1943. Yet with every passing day, they learned of new JGs and fighter groups being relocated from Italy to the Eastern Front, where the Germans were locked in a death struggle with the Red Army as it bore down on the Fatherland.

Germany’s hold on Italy had become a tactical retreat, with Kesselring at its head putting up a valiant struggle that none in the Allied high command had expected. But the demands of the Eastern Front meant Italy would never again be a priority for men or material.

Preparation at Ciampino Airfield

Müller and his three wingmen had been up since 0400 at Ciampino Airfield, just outside Rome. The chill of morning still hung in the air. The Allies had established a tenuous foothold in Anzio, about 50 kilometers to the south, and the mood among the remaining German forces occupying Rome was tense. Outnumbered but not out-planned, the Germans dug in and frustratingly watched the joint British, American, and French forces fail again and again to cooperate effectively. Still, by sheer numbers, the Allies kept the Germans pinned along the Gustav Line. The exhausted soldiers, clad in somber grey, would eventually have to abandon their posts and trudge northward — bracing themselves for the relentless cycle of conflict once more.

Mission Briefing: Target Acquafondata

The four men pulled down and strapped on their canvas flight caps as they walked onto the tarmac toward the waiting Bf 109s, the icy breeze in their faces and the smell of oil and nitrate in the air. It was now 1200. The briefing an hour earlier had revealed their target: Acquafondata, a tiny mountain village 125 kilometers southeast, where a French 155mm cannon threatened the German stronghold at Cassino.

They would approach at 4,500 meters and acquire the target from overhead. Cutting the engines to idle, they would enter a terrifying 80-degree dive, approaching speeds of 560 kph. After 30 seconds of descent, they’d release their bombs 1,000 meters above the target, and the plane’s auto-recovery system would engage, pulling the aircraft out of the dive so quickly that they had to push their heads back into their seats to avoid breaking their jaws on their chests.

Pilots often blacked out briefly at 3–4 Gs as the system engaged. They would be most vulnerable in those seconds, as intelligence reported anti-aircraft batteries in the area.

Müller, the Staffelkapitän, had circulated an aerial photograph of the target during briefing, etching its image into their minds as they mentally rehearsed the assault.

Climbing into their cockpits, the men buckled in. Müller carefully pulled out a picture from his jacket pocket and taped it just above the horizon indicator.

“Guten Morgen, meine Lieben,” he whispered softly, his finger brushing the image of his wife and two children.

He turned the magneto, and the fearsome machine came to life. The familiar drone of the engine grumbled low and ominous. Müller’s Bf 109G had seen action in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. After over 100 sorties, both aircraft and pilot were seasoned veterans. Battle had taken its toll: bullet holes pocked the fuselage, the cockpit manifolds rattled as the Daimler-Benz DB 605 groaned, and chipped green paint revealed bright metal beneath.

After running through the preflight checklist, he signaled readiness. Ground crew removed the chocks. The man gave a thumbs-up, then ran clear.

Takeoff

Müller nudged the throttle forward. The quartet of planes rolled down the runway through low fog. The Gruppe weatherman had judged that the target would be clear. As each aircraft took its turn, they ascended into the mist-shrouded day. Müller, second in line, watched the first plane lift off gracefully, vanishing into the haze. Reaching 60 knots, he eased back on the yoke, feeling the wheels leave the earth. A sense of tranquility washed over him as he climbed eastward. In the south, tendrils of black smoke rose from Anzio — a stark reminder of the Allies’ desperate struggle in their ill-fated push toward Rome.

Flight Over the Liri Valley

Soon the rolling hills of the Liri Valley gave way to the forested peaks of the Apennines and the mist made for a sight that Kurt Müller had never tired of even when he knew he was off to an uncertain fate. Smoke rose from the chimneys of the the farmhouses that dotted the countryside along the road that winded south from Rome.

Just a teenager in 1935, he’d joined the Luftwaffe cadet unit. His fascination with flight had been ignited long ago in the streets of Heidelberg. Enthralled by the tales of Manfred von Richthofen’s daring exploits in WWI, the young Müller dreamed of emulating the legendary fighter ace, known far and wide as the “Red Baron.” Von Richthofen’s legacy would echo through the years, inspiring scores of young men like Müller to take to the skies in Luftwaffe cockpits, each harboring aspirations of emulating their national hero.

Kurt and his wingmates hugged the rugged mountainside as they charted their course eastward before veering south and west towards Acquafondata. Mostly the journey was over thick uninhabited forest, but every now and again they fly over a town, and Kurt could see Italian peasants grabbing their children and rushing to shelter: seeing the black cross on the underside of the wings – a symbol synonymous with German aggression.

It was a blessing and a curse: the BF-109 was easily recognizable as German to both friend and foe; on the Allied side, this was often less so. The Allied soldiers training to recognize a plane as friendly was the pneumonic device WEFT: “Wings. Engine. Fuselage. Tail.” To Allied airmen this become known affectionately as “Wrong. Every. F**cking. Time.” The trigger happy boys on the ground seemed to fire at anything in the sky that moved.

After about 25 minutes into their flight they had reached Castel di Sangro and the three planes ascended to their attack altitude and made a wide sweeping right turn to 200 degrees as they drew closer to the Gustav Line. Kurt looked at the photo, vibrating from the pulsating groans of the engine as it climbed. Recalling the terrain from the morning briefing, he squinted, discerning the silhouette of Monti della Meta on the horizon, its imposing form towering above the forest canopy, serving as a guiding beacon for their approach.

Approaching Aquafondata: The Target Revealed

As they passed over final ridge, he scanned the ground and identified the position of the artillery piece from far above. He gripped the throttle and cut it to idle, the engine responding suddenly as if it had been choked as the plane pointed its nose towards the earth. As the plane dipped, he saw Acquafondata come into view. It was a beautiful little town. Clinging to the hillside. Peaceful as if it were are small little town in the Bavarian alps where he had grown up.

He looked to the right and in the tight formation could see his wingman’s face. “Auf geht’s!”

Engagement and Escalation: Facing Enemy Fire

For a full 30 seconds the plane dove, and as it got closer and closer to the mountains more and more details came into focus. At 1500m above ground, he realized that the artillery position he had identified was not artillery at all, but an abandoned supply depot of some sort. Had the gun been moved? It was not where the intelligence reported from just days before. Instead, a nearby gun emplacement opened fire. Tracer rounds streaked towards him, accompanied by the ominous bursts of flak exploding in the air. The familiar cacophony of metal striking metal echoed through the cockpit as shards of shrapnel peppered the fuselage, a relentless assault sounding like coins hurled against tin.

“Scheiße!”

Now seeing the AA battery below him he squeezed the trigger, realizing that plan B was underway as the primary target was no where to be found: a strafing run to harass the enemy’s positions. As the earth got closer and closer a tableau unfolded: the hunter green tent village to the west of town, the stark white cross atop the makeshift hospital, the orderly chaos of trucks lining the roadside, men lined up outside the mess for chow now scrambling for cover. Amidst it all, the AA battery sprang to life, its crew scrambling to man their guns, unleashing a storm of bullets into the heavens towards them. Below, farmers tending to their livestock scattered for safety, the tranquility of the countryside shattered by the sudden onslaught.

Klank – klank – klank – klank

A stream of bullets quickly pinged through the plane’s fuselage in succession. Amidst the gunfire, he discerned a sound he knew all too well—a shell penetrating a part of the aircraft that posed no threat to its operation. But this time, it was different. The cockpit manifold emitted a menacing hiss, and suddenly, a scalding splash of engine oil obscured his vision like a hot skillet flung into his face. With gritted teeth, he yanked back on the yoke, attempting to pull out of the dive amidst the haze of confusion. His gaze flickered to the right, a sinking feeling gripping him as he saw the unresponsiveness of his ailerons to his desperate commands.

With a surge of desperation, he continued to pull on the yolk and pushed his head back into his seat. Yet, through the veil of oil-slicked goggles, all he saw was a mountainside, looming ever closer. It resembled Bavaria, he thought — those familiar woods, those beautiful mountains. As his hand hesitated over the lever, ready for the final, desperate act of ejection, memories flooded his mind: of hunting in those Bavarian woods as a boy, his father by his side. The birds calling. The crackle of twigs underfoot. It’s funny, he thought for a brief moment, the things that you think about before you die. Moments from impact, he felt the sudden engaging of the auto-recovery system, pulling the plane away from the ground. In a few seconds all went black.

Sources:

- Air War Over Italy – 2000. Andrew Brookes

- World War II in the Mediterranean, 1942-1945 (Major Battles and Campaigns) 1990. by Carlo D’Este (Author), John S. D. Eisenhower (Introduction)

- The Luftwaffe 1933-45. Hitler’s Eagles. 2012. Chris McNab

- Hebenstreit. Messerschmitt Me 109 G-6 fighter of Jagdgeschwader 27 (I./Jg 27; machine of group commander Major Ludwig Franzisket?) with two MG 151/20 under the wings in flight; circa February/March 1944 2024. Wikimedia Commons.

- Belin, Jaques. In the sector of the 3rd DIA (Algerian infantry division), sappers from the 180th BG (engineering battalion) repaired and paved a road leading to the village of Acquafondata. 1944. Photograph. Images Defense. imagesdefense.gouv.fr

- Belin, Jaques. An artillery piece in position not far from the village of Acquafondata. 1944. Photograph. Images Defense. imagesdefense.gouv.fr

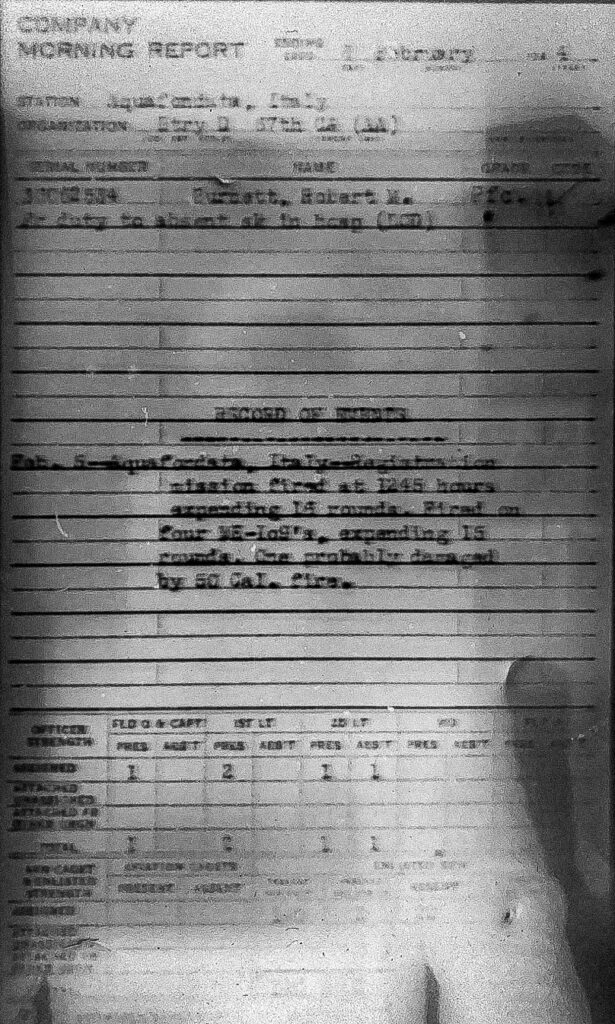

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. “US Army Morning Reports. 67th CA. 1943.”

Text reads:

“Feb 5th – Acquafondata, Italy. Registration mission fired at 1245 hours expending 14 rounds. Fired on four ME-109’s, expending 15 rounds. One probably damaged by 50 Cal. fire.”

WOW, as always a beautifly writen piece giving the feeling you’re right there with them. Love your story telling!

This is not a tribute to the purpose that they served, but one of the men who flew these planes

soaring into the heavens with a fervent passion for flight, becoming pioneers in the sky in a world which had never known such a thing.

Such was the reality of the conflict, where compassion wrestled with duty in the crucible of battle.

He turned the magneto and the fearsome machine came to life.

The familiar cacophony of metal striking metal echoed through the cockpit as shards of shrapnel peppered the fuselage, a relentless assault sounding like coins hurled against tin.

Glad you enjoyed 🙂 Remind you of your Cessna days? 93L was is it?

Gripping story telling, well done!

If you allow my pointing a small typo: it is ‘chocks’ and not ‘chalks’.

Thank you for the feedback and the correction! I have fixed it.

Also the first image of the ‘aircraft’ leaves much to be desired…bad

So I have been told by a few others as well. I had not anticipated so many airplane enthusiasts to view the post 🙂